Programming for Noobs II: Charming the Python

The next installment of our programming adventure! In this guide, we’ll get our hands dirty with actual programming. If you haven’t read the first part, not a problem. Feel free to jump in right here, or go back to check out the command-line wizardry we covered previously.

Audience: curious folks who may (or may not) have read Part I of this series

Source: desktopwalls.net

There are nearly 1000 programming languages in use around the world. Nearly 1000. So where do we begin?

Programming with Python

There’s no perfect answer, but Python is as good a choice as any. It’s

- simple: you’d be hard-pressed to find an easier language to learn

- versatile: use it for anything

- popular: as measured by these people

You’ll find python everywhere, not just software companies, but websites, businesses, Wall Street, research centers1, governments, everywhere. If there’s one programming language to learn, it’s Python.2 If there’s one programming language that will land you a job and earn money, it’s Python.3

So let’s do it.

Setting up

As before, everyone’s computer will be slightly different. The instructions I give here may not work for everyone. If in doubt, Google will be your best friend.

You will need to a terminal. See part I if you need a refresher.

Mac / Linux

If you’re running a *nix system like Mac or Linux, setting up is easy. On Mac, double check you have the package manager4 Homebrew installed. If not, open a terminal and copy in:

/bin/bash -c "$(curl -fsSL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Homebrew/install/master/install.sh)"

Hit enter, then follow the prompts.

After the package manager installs, do

brew install python3

If you’re on Linux, the command is

apt install python3

If you get something that says “Permission denied”, you may need to add

a sudo5 in front of the command. Below is a demonstration of what

your command line will look like — remember that the “$” is not part

of the command, but represents the prompt.

$ sudo brew install python3 # Mac

$ sudo apt install python3 # Linux

To verify that the installation worked, enter the command python3 and you

should see something like:

$ python3

Python 3.5.3 (default, Sep 27 2018, 17:25:39)

[GCC 6.3.0 20170516] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

Hooray! You did it. The “>>>” is the Python REPL6 prompt. Press ctrl-C to quit,

or type exit() then hit enter.

Windows

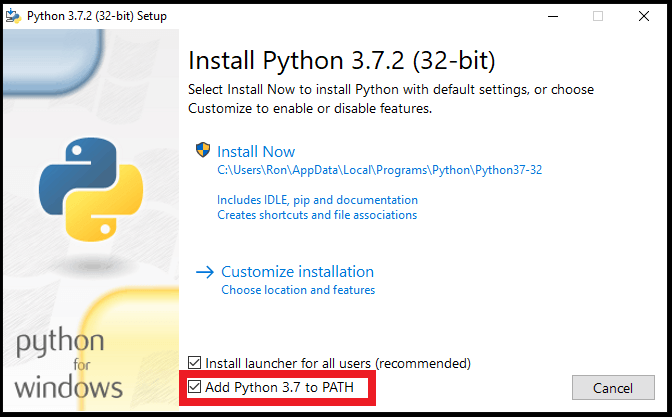

Navigate to Python’s website, go to Downloads, then

find the right installer for your machine, probablyJWindows x86-64 executable installer.

Double-check you’re installing the latest version. (As of this writing, should

say 3.something.)

Download it, run it, follow the prompts to completion. At one point, it may ask whether you’d like to add Python to your system path. Check yes. Then proceed as usual.

Source: datatofish.com

To test your installation, open Powershell

and enter python. You should see:

$ python

Python 3.5.3 (default, Sep 27 2018, 17:25:39)

[GCC 6.3.0 20170516] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

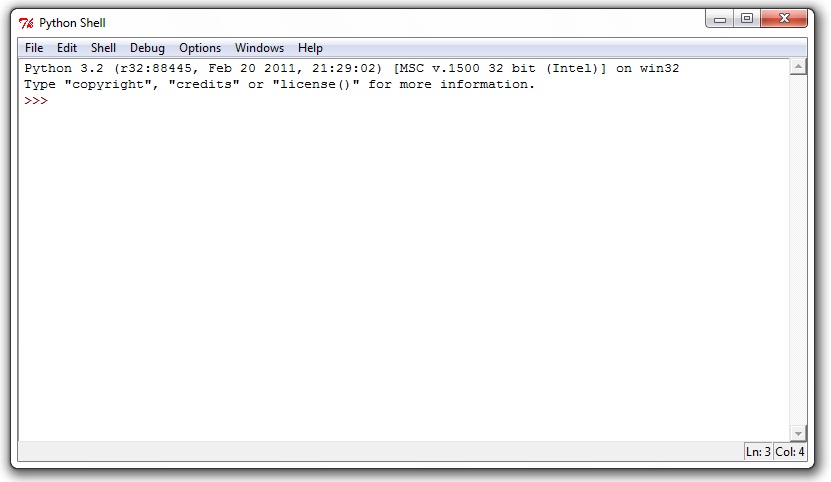

If that doesn’t work, look for an app called “Python IDLE.” Launch it, and you should see the “>>>” prompt as well.

Source: www.cs.uky.edu

Basics

Now for some action! At the Python prompt, type the following and hit enter

>>> 1 + 2

Hopefully you’ll see 3. Great.

There’s a host of math operations you can do:

>>> 1 + 2

>>> 5 - 3

>>> 4 * 2

>>> 6 / 3

>>> 2 ** 3 # exponential

>>> 5 % 2 # modulo

>>> 5 // 2 # round down

# and much, much more

We can store the value of an expression into a variable

>>> value = 1 + 2

The word on the left, “value”, is the name of our variable. Now if we do

>>> print(value)

we get 3 again. The stuff on the left of = is always the name of the variable.

The stuff on the right is always the data being stored. The “print” with

parentheses is a function. More on that later.

Variables don’t have to hold math expressions. They can also store words:

>>> value = 'charm that Python'

>>> print(value)

'charm that Python'

In programming jargon, these words are called strings.7 Strings can

be denoted either with 'single quotes' or "double quotes". They mean

the exact same thing.

Strings can be combined using +

>>> value = 'charm that' + ' Python'

>>> print(value)

'charm that Python'

Numbers can be converted into strings

>>> str(2)

and vice versa

>>> int('2') # for integers

>>> float('2.5') # for decimals

Putting all this together:

>>> value = 1 + 2

>>> message = "value is " + str(value)

>>> print(message)

'value is 3'

Variables can also hold booleans, which are true / false values.

>>> value = True

>>> print(value)

True

Common Data structures

Data structures are programming constructs that store and organize data. Python has a ton of them, but the two most common are lists and dictionaries.

List

A list is a sequence of values. They can be anything

>>> a_list = [1, 2, 3, 'hello', False]

To access an element in a list, use its index

>>> print(a_list[0])

1

>>> print(a_list[3])

'hello'

Note that the first element starts at index 0. If you try to access an index that’s not in the list, you’ll get an error

>>> print(a_list[100])

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

IndexError: list assignment index out of range

Other nifty list operations:

>>> a_list[0] = 10 # set the first element to 10

>>> len(a_list) # get the length of the list

>>> a_list.append('Python') # add 'Python' to the end

>>> a_list[0:2] # get all elements from 0 up to (but not including) 2

Dictionary

Dictionaries store key-value pairs of data

>>> a_dict = {'a_key': 'a_value', 2: 'another_value', 'third_key': True}

Keys are named to the right of the :, values to the left. Keys and values

can be just about anything, but the keys need to be unique. Then to

access values of a dict, we can do

>>> print(a_dict['a_key'])

'a_value'

To add a new key-value pair or set an existing key-value pair, the operation is the same:

>>> a_dict['new_key'] = 'new_value'

>>> print(a_dict['new_key'])

'new_value'

Source files

Most Python isn’t written on a REPL, but in a source file. Use your favorite

text editor to open a file example.py and enter the following

print('Charm the Python.')

Now in your shell:

$ python3 example.py

and out prints Charm the Python.

The file example.py is called a source file. It contains Python code that

can be executed with the python38 (or just python on some machines) command.

Everything that we’ve done previously on the REPL can be written in a source

file instead. Source files intended to be executed on the command line are

often called scripts.

Source files can include comments. These are pieces of text meant for a human reader, not the machine. When you run the script on the command line, all commented text are ignored. Python has 3 different kinds of comments:

# this is a single line comment

value = 1 + 2 # it can come after expressions, too

'''

This is a multi-line comment. It can span

multiple

lines.

The start and end are denoted with three quote characters (').

'''

"""

This is a docstring -- short for documentation string. It's essentially the

same as the multi-line comment above, but using three quotation mark

characters (") is a convention that means this comment is intended to be

documentation to instruct other developers on how to use the code.

"""

Large software projects can include many hundreds of source files, with many hundreds of thousands of lines of code.

Control Flow

Not all code has to run from top to bottom. Python includes many utilities that help direct the flow of code in a source file. Before we dive in, let’s talk about booleans.

Booleans

Remember from before we can assign the values True and False to a

variable. There’s a few operations we can do with booleans, manipulating

their value. For example

>>> value = not True

>>> print(value)

False

The not operator flips the value of the boolean. We also have and and

or operators:

>>> True and False

False

>>> True or False

True

>>> True and not False

True

For more details about boolean operators, check out this post.

Other operators return booleans:

>>> 3 > 2 # True

>>> 3 < 2 # False

>>> 3 >= 2 # "greater than or equal to"

>>> 3 <= 2 # "less than or equal to"

>>> 3 == 3 # equality

>>> 'Python' == 'Python' # works with strings, too

>>> True == True # and of course with booleans, also

If you’re curious to learn more, check out the Wikipedia page on boolean algebra.

Conditionals

Booleans can tell us which segments of code should or shouldn’t be run. One way we

can do this is through if statements:

if True:

# run this code

# indentation is important

# everything indented to this level is run

if False:

# this code does not run

value = 3

if value > 2:

# does this code run?

# Yes! It absolutely does

We can add an else statement after the if to run an alternative block of

code:

if False:

# this code does not run

else:

# but this code does run

If we can also insert zero or more elif (short for “else if”) statements between

the first if and the final else statements:

if False:

# this code does not run

elif True:

# this code does run

# elif is like an else followed by an if

else:

# this code no longer runs

# because the above elif clause is triggered

Conditionals can occur anywhere in your code. There can be code that precedes it, and code that follows it. For example, here’s a simple password checker you can try:

"""

A simple script to check the password.

Copy and paste this into a file called `password.py`

"""

password = "python"

print('Type the password:')

user_input = input()

if password == user_input:

print('Correct!')

else:

print('Wrong!')

print('All done')

The function input() pauses the program until the user types in a string and

hits enter.

One important note, empty lines don’t matter. There can be as many empty lines as you’d like between one chunk of code and the next. But indents do matter:

if password == user_input:

print('Correct!') # WRONG!!!

if password == user_input:

print('Correct!') # Correct

The indent defines a code block. All adjacent lines indented to the same level are in the same block. Python uses this to tell which lines of code to run in a conditional

if password == user_input:

print('Correct!')

print('This also runs')

else:

print('Wrong!')

print('This is part of the same block')

print('This will always print')

Running with the correct password then prints

Correct!

This also runs

This will always print

Loops

Another common way to control which blocks of code run is with loops. As the

name suggests, loops repeat the same block of code. There are two major

kinds: for and while loops.

For loops

For loops look like this:

a_list = ['charm', 'the', 'python', 2, False]

for element in a_list:

print(element)

Running the code yields:

charm

the

python

2

False

The variable element gets assigned to each value in a_list, and executes

the code below per each value. The variable names don’t matter, you could’ve

done for banana in mangoes and that would’ve worked equally well. Commonly,

you might see something like:

for i in range(5):

print(i)

which will print

0

1

2

3

4

You can think of the range(5) part generating something like a list [0, 1, 2, 3, 4].

While loops

While loops look like this:

while condition:

print('one iteration!')

So long as condition is True, the code below will be repeated.

While and for loops are not unique. Every for loop can be written as a while loop. For example, a while loop that mimics the for loop from before:

i = 0

while i < len(a_list):

element = a_list[i]

print(element)

i = i + 1

Question for you: can every while loop be written as a for loop?

While loops open the possibility for infinite loops. For example

while True:

print('This loop will never stop!')

So it’s always important to be careful and check that your loops terminate.

Otherwise empires may rise and fall, the sun darken, the Universe approach

absolute heat death, before your program terminates. If you do fall into an

infinite for loop, press ctrl-C to force Python to die.

Functions

Functions are the bread and butter of programming. They define named chunks of code that carry out certain, well, functions. We’ve seen a few already:

print(): prints a value to the screenlen(): gets the length of a listinput(): takes keyboard input from the userrange(): generates a list-like object of numbers

A programmer’s function is somewhat like a mathematician’s function. From math class, you might remember seeing something like:

$$ f(x) = x + 2$$

Then we can say, for example, that \(f(3) = 5\). You put in a 3, out pops a 5. We can do something similar in Python:

def f(x):

x = x + 2

return x

Let’s tear it apart:

defmarks the beginning of a function declarationfis the name of the functionxis an argument- the indented block of code is the function body, and carries out the actual work

returnspits out the final value

Then we can use it just like the math function:

>>> f(3) # evaluates to 5

>>> y = f(3) # now the variable y has the value 5

But a programmer’s function can be far more powerful than anything from math class. Inside the function body, we can put any kind of Python code we like — conditionals, loops, other function calls, and Python trick we’ve learned so far can be part of a function. So if we wanted to do something a little fancier, say:

def assign_grade(raw_score):

grade = 'NA'

if raw_score > 90:

grade = 'A'

elif raw_score > 80:

grade = 'B'

elif raw_score > 70:

grade = 'C'

elif raw_score > 60:

grade = 'D'

else:

grade = 'F'

return grade

Now we have a nifty function that can convert a raw score into a letter

grade. Whenever we need it, we can call something like assign_grade(93)

and out comes A.

In this way, functions are pieces of reusable code. If you need some kind of functionality over and over again — like converting a raw score into a letter grade — it’s better to write a function and call it, rather than copy-pasting the same code continually.

Functions are also an excellent way to organize code. They attach a name,

like assign_grade, to an important chunk of code. When you use the same

code somewhere else, someone doesn’t have to guess what all those

if-else statements are doing. They can see the name, and know instantly

that it must be assigning grades.

Looking ahead

Congrats! You now have the basic skills to write Python code. But there’s still plenty we haven’t touched. More advanced skills to look into include:

- Object Oriented Programming: a style of organizing code that can make it easier to reason about certain kinds of programming logic

- Modules: how Python organizes source code

- Clean code: writing your code such that it’s easy to update and easy for others to understand

- File I/O

- Regular Expressions

- Graphics

- Scientific Python

- and much, much more…

An excellent resource for further learning: Al Sweigart’s Automate the Boring Stuff with Python. Sweigart covers all the essentials, plus more, and teaches how you can use Python practically to simplify the everyday and humdrum. The whole book is available online at the link.

There’s never truly a stopping point when it comes to programming. This is applies to seasoned developers, too — there’s always something more to learn, another tool to understand. You’ve taken the first few steps into your glorious programming future! And there’s many more to go.

Footnotes

-

Especially in machine learning. As of this writing, Python is the defacto default language for machine learning applications and research. That clever face-recognition app on your phone? Probably started in Python. If you’re curious, check out Tensorflow and PyTorch, two popular Python frameworks for ML ↩︎

-

Python is my favorite, goto language, so I’m biased in this direction. But that doesn’t make it any less true. ↩︎

-

If you’re leaning in the direction of a software career, also consider Javascript. It’s the language of the web, and a must-have for any aspiring web developer. Check out this post for more info. ↩︎

-

Package managers are utilities that help install software. They’re not as common on Windows, but for *nix systems, they’re super convient. ↩︎

-

sudo(pronounced like Sue Doe) is short for “super do.” It’s a nifty command that elevates whatever command that follows to the highest permission, enabling access to sensitive corners of your computer. ↩︎ -

REPL stands for Read-Evaluate-Print-Loop. It’s a standard fixture in many programming languages, and let’s you execute code on-the-fly at a prompt. ↩︎

-

They’re called “strings” because they’re a string of characters. For more tidbits, check out this thread. ↩︎

-

The extra “3” means that we’re using Python version 3. Just calling

pythonusually means version 2. For any new project, you should almost never use Python 2. Stick with the latest and greatest. ↩︎