Programming for n00bs: an introduction to our craft

If you’ve always wanted to learn how to program, but never know where to start, you’re in the right place. Start here. Today is the first day of your glorious programming future.

Audience: curious folks interested in programming

Source: https://www.lynda.com/Programming-Foundations-tutorials

There’s a common myth that programming is polarizing. You either get it or you don’t.

Lies.

Here’s more falsehood: you need to be super smart to learn how to program. Only geeks like programming. Women are rare in this field. You’re too old to learn programming. You’re too young to learn programming.

Anyone — and I mean anyone — can learn how to program.

It’s easy. It’s fun. Sure, you can make a lot of money — but to be honest, no one I know who’s serious about programming is here for $$$.1 It’s a genuinely meaningful activity. There’s creativity, imagination, a chance to sprinkle your thoughts in a text file and watch it spring to life.

In this two-part guide, I will give you the tools (and ideally the mindset) to begin your programming journey. This first part focuses on the command line and other basic skills to start. The second part starts the actual programming.

Whether you’re hoping to pick up a new hobby or gunning for a software engineering future, this is the perfect place to begin.

Big picture stuff

At it’s most general, computer programming is the art of writing instructions.

Two keywords here: art. And instructions. Let’s start with the sexier term: instructions.

In a very real sense, programming is no different than writing a grocery list of goodies you want your spouse to pick up. It’s no different than scribbling a note to your mom, telling her what to get from Subway, or jotting down a cooking recipe to remember for later.2

But instead of your spouse, Mom, or your future self, the audience for our particular instructions are computers. Computers don’t speak English (yet) so it’s up to the programmer to learn their language. That’s the easy part, and the part we’ll focus on in this guide.

The other side, art, is trickier to tap. There’s an art to writing code, just as there’s an art to writing prose. Good code tends to look good, feel good. It’s aesthetic. Expressive. So damn clean you can eat off it. It’s hard to get into the details without first learning some, so we’ll come back to this concept in part II.

But the biggest thing I want you to keep in mind moving forward is this: programming is possible. Sometimes, it’ll seem hard. Sometimes, it’ll seem impossible. Sometimes, you’ll want to smash a hole through your laptop because nothing seems to work right. Don’t. You can do it. And more importantly, laptops are expensive.

Programming requires a different mindset than what you may be used to. It takes time to sink in. Give it a shot, and if it doesn’t make sense, leave it to cook on the back-burners for a little while and come back later. I promise you won’t regret it.

Setting up

Setting up is the hardest part of the journey. Everyone’s machine will be a little different. The instructions I give will try to be general enough to get everyone, but you might have a really cranky laptop that just isn’t feeling it. In that case, Google and Stack Overflow will be your best bet.

The single most important thing you’ll need is a terminal. Fortunately, your computer should come equipped with one. Unfortunately, they’ll all be a little different depending on your operating system.

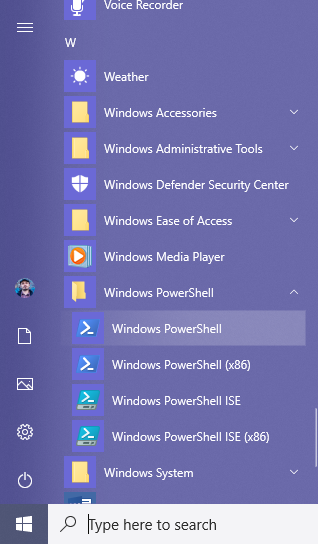

If you’re running Windows, you have three options:

- cmd

- PowerShell

- Windows Subsystem for Linux

The first two come with Windows. Open up your applications menu or search box, and you’ll find them.

Source: https://www.digitalcitizen.life/ways-launch-powershell-windows-admin

However, if you don’t mind installing a little extra gear, I recommend option 3. To get it, open up your Windows Store app, search for Ubuntu on Windows, and install it. This application isn’t a simple terminal, but will emulate a whole operating system (Linux) for you. Using it will allow you to follow the rest of this guide with minimal headaches.

If you prefer to stick with the native Windows options, I’d take PowerShell. It’s far more advanced, and will play nicer with the instructions I will shortly give for using your terminal. If, for some reason, you’re married to cmd, you’re on your own, but you can learn more about it here.

If you’re running macOS, things are a lot simpler. The terminal is called “Terminal” (go figure) and is easily searchable with Spotlight (ctrl + spacebar).

And if you’re running a flavor of Linux, terminals will differ between distros, but you’re likely proficient enough anyway to know how to use one.

Next, you’ll need a text editor. It’s a program that allows you to write text into files, and it’s the Swiss Army Knife of coding. Most computers will have ones built-in, but you’ll need something with a little more power than Notepad to do proper work.

My personal favorite is Atom. It’s slick. Hackable. Easy. And I’m using it right now to write this post.

If you’re willing to shell out some cash, another popular editor is Sublime. It’s an industry favorite, but comes with a hefty price tag. Why pay when Atom is just as excellent, and free?

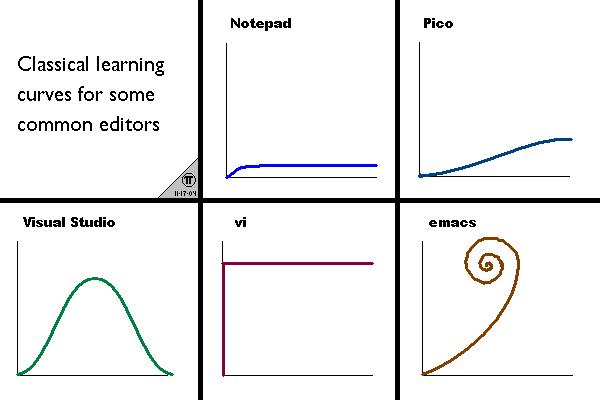

And for the hard-core, there’s Vim.

Source: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/10942008/what-does-emacs-learning-curve-actually-look-like

It’s infamous for being tough to learn. But master it’s wizardry, and you’ll blaze with obscene speed. If you’re prepared for an epic challenge, here is my favorite tutorial for the editor.

Take some time to learn your chosen editor. They’re often geared towards programming, but you can use them for just about anything word-related. Write your essays with them, if you’d like. Compose poetry.3

Once you’re ready, let’s sink our teeth into some serious work.

Shell

A terminal is a special environment that runs a program called a shell. In the old days, a terminal was a physical device attached to a computer. Today, you can access one through a window on your screen.

A shell is a special kind of program that launches other programs. You’re running a shell right now. On Windows, it’s called “Windows shell,” and it’s the familiar environment you use to interact with your computer. The desktop. File explorer. Login window. All of it is part of the shell. Using it, you can double-click on an icon to launch a program.

But the kinds of shells we’re interested in are called “command-line shells,” or sometimes “command-line interface” (CLI). Whereas the Windows shell is graphical, CLI’s are text-based. There are no fancy desktops. No icons. No clicking. To launch a program, you type its name and hit enter. From here on out, when I use the word “shell,” I’m referring to these text-based versions.

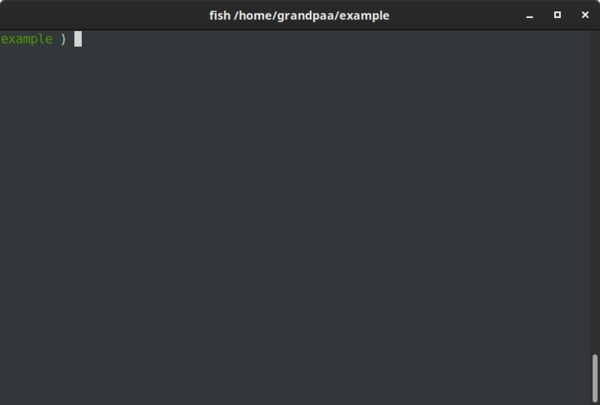

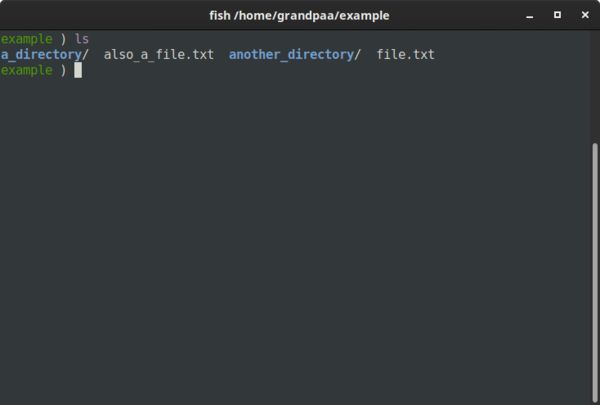

PowerShell and Mac’s Terminal are terminals that run these text-based shells. Open one right now, and here’s what you might see:

Source: me

Yours will likely look a little different, but the basic gist should be the

same: a blinking cursor in front of a prompt. Try typing ls and hit

enter. Mine looks like this:

Source: me

Yours will differ, depending on the files in your system. To save myself some space, I can also use a convention to write the output like this:

$ ls

a_directory/ another_directory/ file.txt also_a_file.txt

The “$” represents the prompt. A line without “$” signifies output.

So what just happened?

Unlike a graphical shell, where we can double-click an icon to launch a program, to launch a program in our text-based shell, we need to type the name and hit enter.

In the example above, we launched a program called ls, short for

“list files.” To understand what this means, let’s talk about files and

directories.

Files and Directories

The data in your laptop are organized into files and directories — “directory,” by the way, is another word for “folder.” CS folks just prefer “directory” for reasons of taste and style.

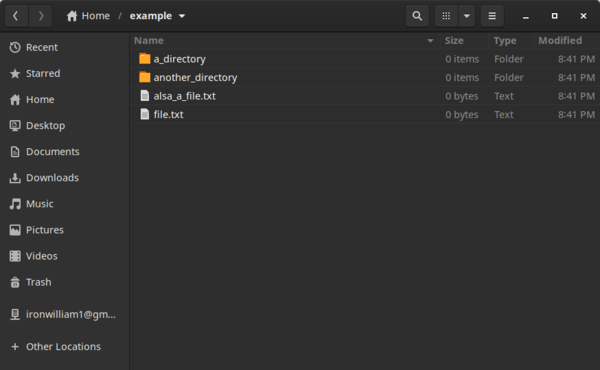

If you open your file explorer, you’ll see a bunch of them. Here’s what I see:

Source: me

Files are blobs of data collected in place. In the example above, there are two text files. They don’t have to be just text. Laying around my computer, I’ve got images, music, video, PDFs, programs — all are files.

Directories are special structures that hold other files and directories. In the image above, there are two directories marked by little folder icons. In your file explorer, you might be able to double-click a directory to open, and see what’s inside.

Every file and directory in your computer is housed in the root directory.

It’s a humongous directory that contains everything else. In Windows, it’s

called C:\. In macOS or Linux, it’s simply /.

Every file and directory also has an address, called a path. A path is a

string of directory names leading to the location of a particular file

or directory. The path to the root directory would simply be / (assuming

we’re using a Mac or Linux). If we had a directory called “home” within the

root directory, its path would be /home. Inside the home directory, we

might have another directory called “wlt.” It’s path would be /home/wlt.

Inside wlt, if we had a text file called “sample.txt,” its path would be

/home/wlt/sample.txt.

Windows’ paths look a little different. Instead of beginning with a /, the

root directory on Windows is C:\. Instead of forward slashes /, Windows uses

backslashes \ to separate directory names. Our example on Windows would look

like C:\home\wlt\sample.txt.

Return to your terminal, type pwd, and hit enter. I get:

$ pwd

/home/wlt/example

pwd stands for “print working directory.” Your terminal squats in a directory

when executing commands, and pwd prints the path to this directory. In this

case, we’re sitting in a directory called “example” that’s nested within wlt,

which in turn is nested within home, which is located in the root directory.

Remember from before, the command ls? When it executes, it lists the files

in your current working directory. So when I did:

$ ls

a_directory/ another_directory/ file.txt also_a_file.txt

I’m listing files in example. The path to the directory a_directory would be

/home/wlt/example/a_directory.

A note on terminology, when talking about paths, we were really talking about absolute paths. An absolute path is one that describes the chain of directories starting from the root directory.

Alternatively, a relative path is a path described from the current working directory.

For example, located in example, the absolute path to file.txt is

/home/wlt/example/file.txt, but its relative path would simply be file.txt,

because the file is located directly in our current working directory. If

file.txt were located in a_directory, it’s relative path would instead

be a_directory/file.txt.

Simple commands

Now that we have a handle on the file system, we can start learning basic commands with the terminal.

Remember that a command is nothing more than a simple program, like Microsoft Word or your Internet browser. To execute a program in a shell, you simply have to type its name and hit enter. Try it:

$ notepad

If you’re on Windows, that command should have launched your Notepad text editor. If you’re on Mac or Linux, try this instead:

$ vi

This command launches the Vim text editor (or it’s predecessor, vi) To exit,

type :q.

To customize how a command behaves, you can add additional options. These

are basically extra words or letters we can tag to the end of commands for

bonus functionality. For example, recall from before we can use ls to list the

contents of our current working directory.

$ ls

a_directory/ another_directory/ file.txt also_a_file.txt

If I wanted a little more information about each file, I can do:

$ ls -l

drwxr-xr-x 2 wlt wlt 4096 Feb 3 5:58 a_directory/

drwxr-xr-x 2 wlt wlt 4096 Feb 2 19:40 another_directory/

-rw-r--r-- 1 wlt wlt 156 Jan 30 8:01 also_a_file.txt

-rw-r--r-- 1 wlt wlt 38 Feb 1 12:52 file.txt

The -l option stands for “long,” and it tells ls to list extra details about

each file. Options will usually be preceded by a dash - or sometimes two

if the option is in “long form,” i.e. typed out as in something like --color.

Related to options, many commands take arguments. These are targets that a

command acts on, and are often appended to the very end of a command. For

example, ls can take an argument that specifies what file exactly to list:

$ ls -l a_directory

-rw-r--r-- 1 wlt wlt 5 Feb 5 20:07 deep_magic.txt

-rw-r--r-- 1 wlt wlt 12 Feb 5 20:07 stuff.txt

Note that I’ve used the option -l again, giving us the long form of the data.

It’s also nifty to note that most terminals offer tab-completion. It allows you

to type a partial name, then press tab to quickly fill out the rest. In typing the

above command, for example, I simply typed ls -l a_dir then pressed tab. Magic!

Another nifty command to learn is cd, which stands for “change directory.”4

It changes your current working directory to a different one. To use it,

you specify your target directory as an argument. So if I do:

$ cd a_directory

I’m now located in the directory a_directory. I could’ve also specified

absolute paths:

# with an absolute path:

$ cd /home/wlt/example/a_directory

# with a relative path:

$ cd a_directory

There’s a special file called .. (two periods) in every single directory

that links to the directory above. If I cd into it, I change my current

directory to the one above. For example:

$ cd a_directory

$ cd ..

# I'm back where I started!

You can chain together ..’s to rise multiple levels up the hierarchy at once:

$ pwd

/home/wlt/example

$ cd ../..

$ pwd

/home

There’s another special symbol called a tilde ~. It should be on the

upper left-hand side of your keyboard. The tilde represents your home directory,

a special directory set aside just for you that contains all your personal

files. To get there, do

$ cd ~

Like with other files, you can chain the tilde into paths:

$ cd ~/a_directory

Play around with cd, ls, and pwd in your shell until you get comfortable

using them. They will be the bread and butter of your workflow, allowing you to

swim smoothly through your filesystem with minimal effort. It may feel awkward

now, but soon you’ll be faster with your terminal than the graphical

file explorers you’re used to.

Other useful commands

A few last ones to know before we wrap up:

Moving files: mv. It takes two arguments: a source and a destination.

$ mv file.txt a_directory

file.txt is now located in a_directory.

mv is also the most common way to rename files.

$ mv file.txt awesome.txt

Because awesome.txt did not exist, mv went ahead and created a new file

called awesome.txt and transferred the contents of file.txt over,

effectively renaming the file.5

Copying files: cp. It also takes two arguments: a source and a destination.

$ cp file.txt a_directory

There is now a copy of file.txt in a_directory.

If I want to copy an entire directory, I have to specify an extra option

-r, which stands for “recursive.”

$ cp -r a_directory another_directory

If I wanted to copy a file or directory into my current working directory, I

can use the special symbol . 6

$ cp /some/distant/file.txt .

Making directories: mkdir. It takes one argument: the name of the new directory.

$ mkdir new_directory

There’s is now a fresh new_directory in our workspace.

Removing files: rm. It takes one argument: the name of the file to be removed.

$ rm file.txt

file.txt has now been consigned to the void.

To remove directories, you’ll again need to specify a -r to perform the operation

recursively.

$ rm -r a_directory

And that’s probably the most dangerous command I’ve taught you. One careless

keystroke and your project is lost forever (almost).

A much safer alternative is rmdir

$ rmdir a_directory

but the directory in question must be empty in order for the command to operate.

It’s an extra safety-precaution to ensure you don’t do anything stupid, and I

wholeheartedly advocate its use. But I get lazy too, and sometimes it’s just

easier to rm -r things into oblivion.

And finally, probably the most useful command you will ever use, man. It’s

short for “manual” and gives you a help page on any command. Forget how to use

ls? No problem:

$ man ls

Wanna learn more about man itself? It’s got you covered:

$ man man

These basic commands will probably be about 75 percent of everything you do on a terminal. Again, things will feel awkward and slow at first, but give it time. Before you know it, you’ll be a blazing wizard at the command line.

If you’re interested in learning more, there’s tons of great resources out there. If you’re using Mac or Linux, check out this awesome guide. For Windows PowerShell users, here’s a nice tutorial.

Looking ahead

And that about wraps things up for part 1.

You must be wondering, a whole blog post and not a single line of code in sight? Instead, we wasted a whole lot of nothing on learning the command line.

Why?

Here’s the thing – programming is never just opening a magic program and typing code that just works. It’s built with tools. These tools take time to learn. What I’m teaching you are real tools that real software engineers use. No kiddy stuff here, we’re working with the real deal.

What’s more, if you’re looking into a career in software, you’ll be learning tools like these the rest of your life. Countless tools. Countless programs they help write. We’ve started with the most common set that drives everything else. Learn the command line, and you’re well on your way to mastering anything else.

Next time, we’ll start diving into actual code. Stay tuned, I’ll link the post below as soon as it’s written.7

Footnotes

Here are some stray thoughts that didn’t make it into the normal flow of prose. These are completely optional, but may add color to your reading.

-

That’s actually a half-lie. I got to school in New York. There’s plenty of Financial Engineering majors on campus learning CS for Wall Street, but of the dedicated, hard-core software folks I know, we’re all in it for the love. ↩︎

-

In fact, there’s a programming language out there that looks exactly like writing a recipe. It’s called chef. ↩︎

-

I had a teacher once that used Vim for everything. Lecture notes. Exams. Homework. Love letters to his wife. You name it, he used Vim to write it.

Maybe not actually the love letters, but everything else, I promise. ↩︎

-

The commands I’ll outlining are with a shell called Bash. It’s popular on Linux and macOS. If you’re using Windows’ PowerShell, the commands should still work, but you can find their proper equivalents here ↩︎

-

BE CAREFUL THOUGH! If

awesome.txtreally did exist before, I would have overwritten its original content with that offile.txt. ↩︎ -

In summary, there are 3 special symbols we talked about:

..,~, and.. Each of them are like a shorthand for a path...represents the directory above.~represents the home directory, and.represents the current working directory. ↩︎ -

Still on its way, I promise! ↩︎